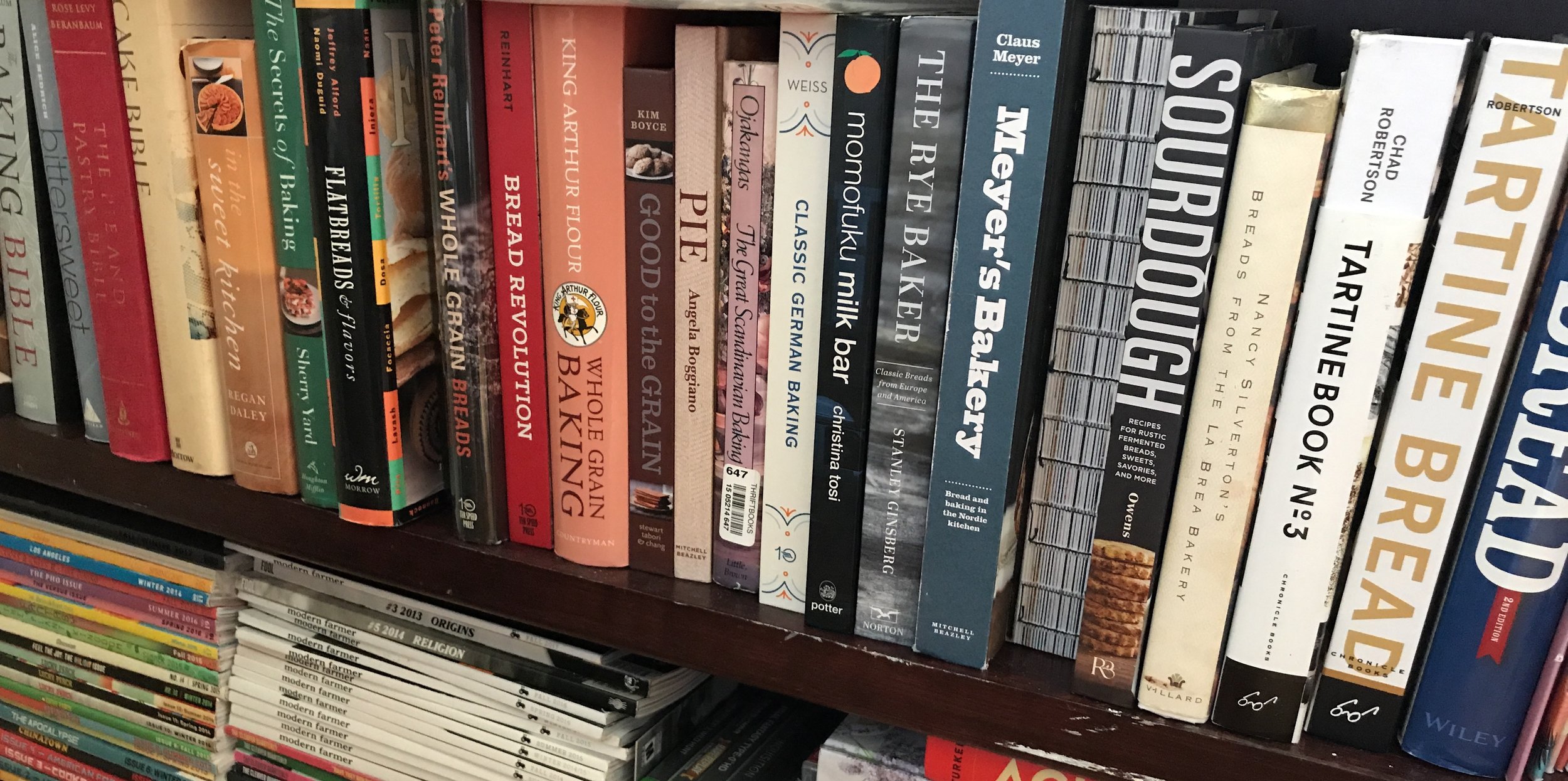

Common and Uncommon Apples, Cookbooks, and Seaweed.

After my last post about cookbooks, it appears that would be the logical place to start this post: with the announcement that Pantry and Palate: Remembering and Rediscovering Acadian Food has been nominated for a Taste Canada Award in the Regional/Cultural Cookbook category.

Taking a look at the nominees, that’s quite the company to keep.

* * *

I’ve written before about being lucky enough to have grown up with an apple orchard in my backyard. My parents have a hobby orchard in my hometown of Pointe-de-l’Église, and so the act of picking an apple directly from a tree is not only familiar, but borderline necessary for me. The snap of biting into an apple is only secondary in pleasure to gentle crack of taking the apple from the branch.

And so I would argue that Gravenstein apples are - to me - best picked a few days early, when they are almost bracingly acidic, but also at their crispest. That McIntosh isn’t worth buying in a supermarket when you’ve eaten one that was only on the tree within a 24 hour window. That Russets - of all sorts - are almost apples designed for adults with their tight texture, gentle dryness, and so many ways of using them. It’s what made me want to write this piece for Canadian Living magazine, entitled “The Apples You Should Be Shopping For This Fall.” *

Old Fashioned Gravensteins

Many thanks to Anita Stewart, Canada’s Food Laureate and maven behind Food Day Canada, as well as Rowan Jacobsen, author of “Apples of Uncommon Character” to being available to talk about the beauty of apples, and how diverse that beauty is.

Also, I do have to admit, I do take a small bit of personal joy in having an image of my father’s Old Fashioned Gravensteins take centre stage. Conflict of interest? Maybe. But I am my father’s son.

That piece went live on the very same day that it was reported that the Red Delicious was on its way out as the best selling apple in North America. Serendipity being what it is, I got a call from a producer at CBC Radio’s As It Happens, asking if I would talk about the Red Delicious, and why it may deserve it’s not-so-gentle tumble from first place. Although it may have been “delicious” at some point in it’s trajectory from one lone tree to the most-grown, success changed the apple, and also changed how we consume them.

Yesterday was also publication day for another story I filed, this time for The Huffington Post, on seaweeds/sea vegetables.

To be clear: 'Superfood' is put in quotation marks for a reason. *

People are looking at them for all sorts of resources - from nutrition to medicine, from ecological as well as gastronomical - but will it work? I chatted with a few people to talk about the eating of it, such as Nancy Singleton Hachisu - author of the recent Japan: The Cookbook, as well as Jonathan Kauffman, who’s book Hippie Food: How Back To The Landers, Longhairs and Revolutionaries Changed the Way We Eat is a treat. I also had a great time Skype-ing with Tamar Haspel, who gave me some of the best quotes for the piece. Haspel’s work over at the Washington Post has earned her a James Beard Award, and her Twitter feed is worth checking out for her no-nonsense approach to agricultural/food issues. Agree with her or not, she has a deft turn of the pen/keyboard.

Recipe for rose sugar - hang out with your mother on the coast of Saint Mary's Bay, collect wild roses. Place in sugar.

In the meantime, enjoy the summer in whatever way works best for you. I’ll be putting up everything I can get my hands on, probably with the rose sugar I recently put together. Thanks to my friend Stephen Sherman Wade for the inspiration. The last of the strawberries have benefited greatly from it, as did my mother and I as we collected the petals...

* It should be noted that writers and journalists rarely select the titles of their journalistic endeavours, and even less so in a landscape that is powered by searchable results. I don’t blame my editor for any titles, and I don’t envy their position either.