New Things for Spring: A book, a tour, and a talk or two

An excerpt from Pantry and Palate, coming soon to a bookstore near you...

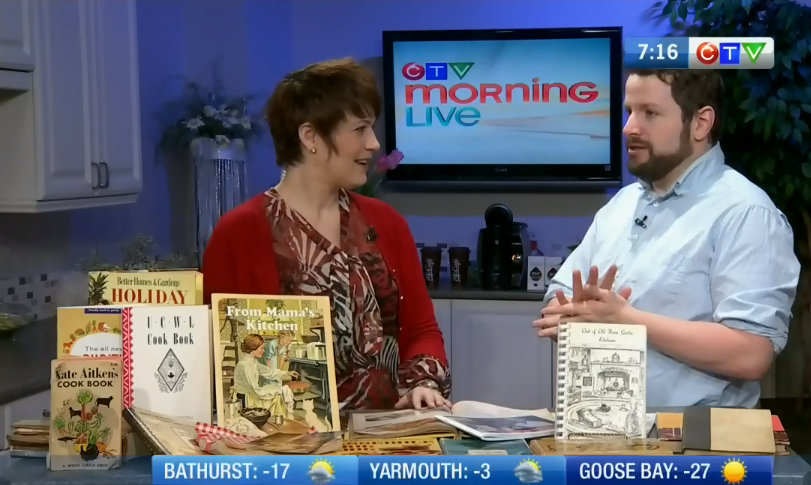

After over two years of research, cooking, writing, editing - and a lovely photo session - Pantry and Palate is finally hitting bookshelves in May.

Because I've spent so much time living within that book for so long, I will admit I am at a bit of a loss for words when it comes to tell you what it's like to live outside of it. The work is done. The book is being printed and bound as I type this. I will have a copy in my hands in a couple weeks. Copies of it will be sent to pre-sale buyers in Canada after May 30th. You can pre-order your copy at Amazon.ca, over at Indigo.ca and via Nimbus Publishing. But for those of you who can wait until it's in stores, might I suggest you check out your local independent bookstore? It's always a good idea.

But the buzz has already started. Chatelaine magazine mentioned it in their 10 Cookbooks We Want This Spring and Amazon has listed it in their Hot New Releases in Canadian Cookbooks. And the book isn't even out on shelves yet. (Excuse me while someone helps me pick my jaw up off the floor.)

Now begins the promotional part of the book, and I'm headed to the Terroir Symposium in Toronto on May 29th at the Art Gallery Of Ontario. I'll be on a panel with other speakers reflecting on the origins of French-Canadian cuisine (and Acadian as well!) and its current path. It also looks like I'll be doing some interviews and a bit of promotional work while I am there.

After that I am off to New York with the gang from Nimbus Publishing to Book Expo America where I'll be signing copies of Pantry and Palate. And if I know myself, I'll be heading to a few bookstores - namely Kitchen Arts And Letters and Bonnie Slotnick - to fill up my suitcase for the trip home. Last time I went, I kind of went overboard and ended up paying $100 at the airport because my luggage was over. But lesson learned: bring an empty carry-on just for books.

But my favourite upcoming event is happening here in Halifax, with a book launch at the Halifax Public Library's Central Branch. I'll be talking about the process of how the book came to be, the importance of culinary history, documenting food ways, and of course, serving up a wee bit of grub.

Now that the book is in the can - I should be holding a copy in my hands in the next week or so - expect to see more updates, more stories, and more info about Pantry and Palate and much more. Stay tuned!