Trusting your head, your heart, and your hands.

Talking, writing, doing, and dealing with food is all about trust - trusting you have the right story, words, the right seasoning, the right touch.

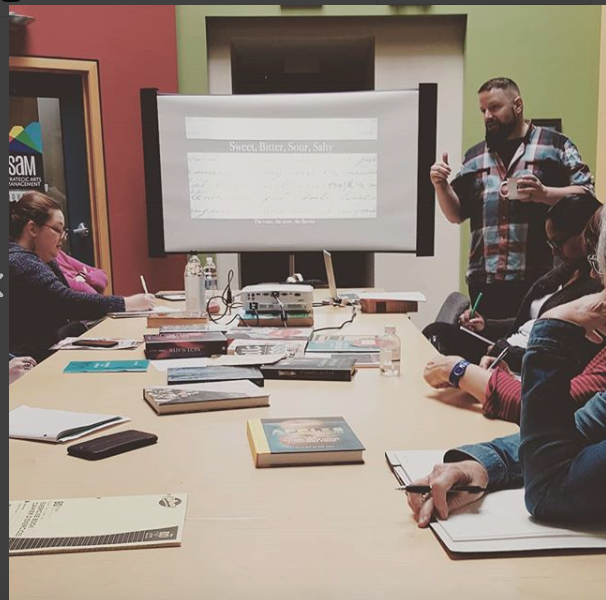

That trust is what I talked about in a recent Saturday that I spent at the Writers Federation of Nova Scotia, teaching a workshop on food writing.

Many thanks to Sara Jewell for the image.

About a dozen people showed up, and we talked about everything from nostalgia to ethics, culinary history to personal storytelling, and everything in between. I brought up classic examples of food writing from Brillat-Savarin to MFK Fisher, culinary historians and chroniclers like Paula Wolfert, as well as contemporary writers like Julia Turshen and Nik Sharma. I wanted to show that food writing is as varied as it’s authors, and that it’s scope is more than just a recipe that tells you to dump and stir.

I’d like to thank the WFNS for having me, and for the wonderful group that showed up. If all goes well, I’ll be teaching other workshops like this one later on in the new year.

But back to cooking, and to the seasons:

A box of fragrant quinces from my parents’ orchard.

I can’t decide if fall is for the heart, or the head.

I’ve closed the windows in my apartment, but the oven door is in a state of constant flux. Open and close, baked goods in and out. Fall makes us want to settle in, ruffle pillows and blankets to warm us, and seek out sources of heat. The biggest source of heat in my apartment these days is my oven.

And I think my heart likes it that way.

This isn’t to say that my relationship to my oven is strictly emotional. In fact, these days my head is swimming with ratios, queries, decisions, calculations.

I’ve been working on a recipe for a whole grain cornmeal skillet cake, something which at first seemed pretty basic. It all started with a recipe from Erin French’s The Lost Kitchen (Sidenote: if you grew up in/near the New England states, or Atlantic Canada, do yourself a favour and read it, as so much of it will sing to you).

I’ve bastardized her recipe, replacing this with that, trying this ingredient with another. Part of it is hubris: I want to see what I can make. How far can I adapt, what can I learn in playing around? But the other part is an exercise in humility: the cake is not where I want it to be. There is much work to be done, things to tweak, figure, play with. I won’t ignore the original, and when people ask where I got the idea, I make sure they know it started with that recipe. But a really good recipe can give you a bit of agency, a bit of liberty. And if you really want to see what you can do, and you pay attention while you’re doing it, the head will lead the heart to a place where both can speak. I fell in love with possibilities, and I enjoy the thought process. I’ll let you know when my head and the heart both enjoy the cake.

I recently had an exercise in letting my heart, or more precisely my hands, lead the way, without thinking too hard. I trusted that I could do it if I just let it be.

My friend Pat had contacted me a few months ago about a french-language television show he was working on. I won’t get too much into details, but let’s just say it involves hunting, a house that’s off-grid, and a bunch of hungry mouths to feed. Now I knew about the hungry mouths, but I was expecting six, maybe eight. Nope. By the time things got underway, there were over a dozen people to feed.

Ok then.

I’m used to knowing where the pots and pans are, used to the amount and variety of ingredients I have in the house, how heavy the cake pan is, how hot my oven runs. But this wasn’t my kitchen. I was making a fricot - a hearty acadian stew - but this time I was making it with partridges they had caught.

One of the aforementioned partridges - technically a grouse, but we colloquially call them “pardrix” amongst ourselves in french-speaking southwestern Nova Scotia.

Have I mentioned I’ve never cooked partridge before?

I mean, I’ve had it, as I grew up in a household where it was present, along with a lot of other forms of wild game. The flavours, the challenges of cooking with game are not uncommon to me, and thankfully not too intimidating. But I was asked to make a fricot with said partidges. And even though I’ve written a book that features fricot, I’ve not made it umpteen times like many of the people who would be sitting at this table would’ve. These were my people - a table of Acadians, not to mention a few extra crew members who had never had the dish before.

So I winged it, no hunting puns intended.

I sautéed onions, more onions than I thought I might need. When making soup, you can never have too many onions. I seared the meat ever so slightly, to create the beginnings of a fond, that rich meaty base for so many soups. I added the water, a carrot or two for flavour, and let it simmer. Once the partridge was cooked, Pat and I took the meat off the bones - those tiny, tiny bones - and put them aside while the broth simmered away, reducing ever so gently. He and I rasped the potatoes for the potato dumplings, or poutines for our fricot au poutines rapées à la perdrix. While the fricot was cooking, the broth reducing and slowly growing in flavour, I started to work on the pies. And this is where my hesitation was put aside.

Like I said earlier, this wasn’t my kitchen. I didn’t have the comfort of my mixer, let alone a pastry cutter/blender. I’m of a generation that relies on machines to do the work for me in a kitchen. A stand mixer, immersion blender, tools that give you time and ease. I had flour, lard, a couple eggs, a bag of apples, and my hands. And to be honest, I learned to stop using my head, and trust my heart. Or rather the next best thing: my hands.

I have to admit, the capacity to trust my hands has taken time. That agency I mentioned above? It’s not an overnight thing. It takes time. Trust in one’s self. And a gentle push.

At that moment in time, that push was feeding people, and not fucking up in front of cameras.

My hands knew to cut the lard into small pieces, and that it should feel a certain way when mixed into the flour. They knew the dough needed just a bit more water to come into it’s shape. My stand mixer would’ve told me to look, but my hands told me more than I can glean from looking. In fact, this felt way more usable, practical, and doable than any other pie I’ve made.

Before you ask, of course I was nervous. This wasn’t a recipe testing session for just me and myself, or a family gathering where I could pawn it off. This was for an audience, an audience of people in this room, and for the people who would be watching this later on television.

Did I mention that I was doing all this cooking with a camera crew following my every step?

But I’d read the recipe before. Heck, I’d written it. But it was in the doing, not the reading or writing, that it felt right.

The aforementioned pies, via Pat’s IG feed.

The pies turned out great. In fact, these were some of the flakiest pies I’ve ever made. Because I was gentle with the dough, because I pushed myself, just a little, because my hands, my head, and my heart, told me that I could, and should.