Lost in pages

I can’t decide if the first joy of a cookbook is in purchasing it, reading it, or in cooking the first recipe from it.

When people ask me about my love for cookbooks, there is a familiar refrain that comes out: I read them like novels.

When I say this, it is to convey the engagement I have with cookbooks: I read them from cover to cover, pore over the language, and the ideas found therein. I want to convey the love I have for these books: the work that goes into making them, and the work that comes out of from using them.

People often have bookshelves stationed prominently in their homes. Those shelves can tell you what language they enjoy, what stories, what ideas. Do they prefer a clipped lexicon, direct and forthwith? Are they fans of flowery language, with sentences that run on to the point of droning verbiage?

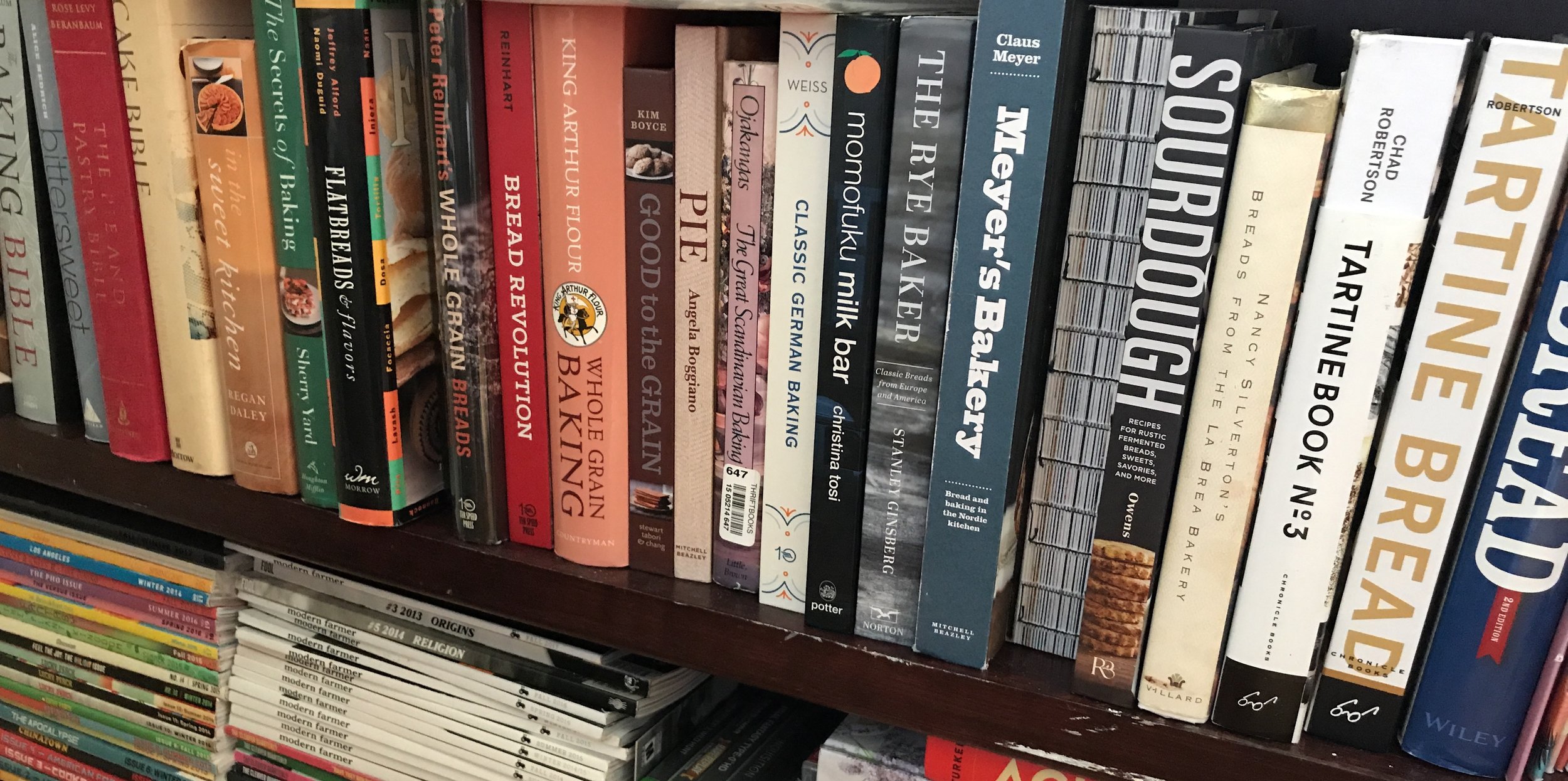

The most visible, accessible, and used bookshelves in my household are filled with cookbooks. The shelves are organized by (loose) categories: a shelf for baking (this is the most rapidly expanding shelf), a shelf organized by regional cuisines, a shelf for books by cooks/restaurants, a shelf for single subjects, and a shelf for resource materials. In my bedroom there are shelves for food writing, books to pick at before bed or books to sit in the sun and absorb their information at the same rate as the sun’s rays come down on me. Deliberately.

The purpose of a cookbook is ostensibly to collate a series of recipes and present them in the best possible manner. Sometimes that manner is direct, with little artifice, and pure information. Sometimes the manner meanders, wafting through your mind like aromas from warm kitchens.

What makes a cookbook valuable is more than just the recipe. It is the perfect example of something being greater than the sum of its parts.

And that brings me to the most common argument I receive when I say that I love and collect cookbooks: I could just look it up online.

Of course you could.

First, let me applaud you. You want to cook, you have a desire to look up a recipe, to try and cook something that is perhaps new to you. Maybe you’ve decided that you want to ameliorate the dish you’ve been making by rote, and are looking for a new way to look at that dish you love. Maybe you are looking at recipes because you need to stretch your dollar as far as it can go. More than anything I applaud the desire to find agency and self reliance, and a respect for the foodstuffs that we have access to, and respect to those who brought them to our tables.

Online resources abound for the curious cook. There are so many websites that can give you instant, practical, and well-tested recipes. I respect, admire, and even wish to perhaps one day contribute to some of them. (That was a hint, editors.) But the manner in which we absorb that information - as immediately and as quickly as we plug in our search parameters - ignores the work that brought it to your screen. More importantly, by ignoring that kind of work, we often ignore the work we are about to undertake ourselves. Or at the very least (or most?) we will view that work as drudgery, a means to an end.

Search. Find recipe. Execute. Eat.

Reading a recipe online is like reading an excerpt from a novel - it can be beautiful, it can lead to satisfaction, but it misses so much of the breadth that gives an excerpt heft and gravitas: the words that surround it on both sides of its cut.

It’s a little too utilitarian. It leans towards the gross rather than the subtle.

So allow me to flip the narrative , and give you a gross of subtleties.

A glut of rhubarb, roasted with ginger and star anise.

Think of how you read a novel. You start at the beginning, and allow yourself to follow the story. You will give yourself permission to pause at certain moments, re-read passages that have struck you. You will follow the narrative flow: Character goes on journey. Character encounters tension. Character resolves issue, completing journey. It is engrossing.

In a good cookbook, there will be a similar flow. Not all books follow a direct narrative approach, nor do they need to. But they follow a logical order: This is what you are here to learn. Here is the process you can follow. Journey complete. Let’s eat.

Like I said at the start of this piece: I can’t decide if the first joy of a cookbook is in purchasing it, reading it, or in cooking the first recipe from it. I think the ambiguity and almost Venn Diagram-esque way of measuring this is part of the beauty. Each book is different, each first joy is different, and each brings about their own nuanced manner of introduction. The recipes don’t stand alone: they stand next to each other, on the pages that precede and proceed.

It could be the location where you sit and read said book. The book may act as a balm to a busy day, helping you leave the world behind, as deeply as you would fall into a novel. It can be even more engrossing than fiction, because unlike fiction where you must imagine the reality, with a cookbook you can forge that reality: at your fingertips, at knifepoint, in the well of a spoon.

There is something to be said for finding that book you’ve been looking for, an author whose name has been repeated to you. For you, it could be an old paperback copy of Elizabeth David, or an out of print tome that you already own, but wish to purchase so that you can give it to someone else. These are two distinct pleasures on their own. Sometimes that book is one already sitting on your shelf, something you picked up because you feel you should own it, or something someone gave you, because they felt you should own it.

For me, the most recent that book was Nigel Slater’s Tender.* Reading it was like listening to that friend who you call when you’re stuck on what to cook next. The one who gives you all the good ideas, and then you actually feel like you can make them happen. At the time of this writing, it’s summer, and I find myself at the edge of a glut: the berries have just begun to appear, and I am at the edge of where I am almost tired of rhubarb. But I don’t wish to be in the case of the latter, and I wish to be prepared for the former.

Yes, it would be easy to type in a few letters and find the most popular recipe for said ingredient. But an algorithm will not tell me what is already in my home, nor will it be able to predict that I will find much more satisfaction in doing my own digging, than letting someone else do the work for me. The satisfaction of looking for the book that holds the recipe for the dish you’ve always wanted to make, or the dish you never thought of making.

This is how you end up with a rhubarb flavoured with amaro. Rhubarb roasted gently with fresh ginger and star anise. Rhubarb baked into various forms of coffee cakes, with various flours to see which works best. I see possibilities, not culinary doldrums.

100% whole grain flour coffee cake with rhubarb roasted with ginger and star anise, and an oat and oat flour streusel.

This is how your fridge is emptied. This is how you become emboldened. Like a novel that leaves you with hopes and ideas, a cookbook that has been read from cover to cover can arm you with knowledge and inspiration.

Because you allowed yourself to once again get lost in pages.

* I could link to an online retailer here, but really, if you care about books as much as I think you do, you could ask your local retailer to order it for you, or at the very least, check it out of your local library.